The Modern Study of Mishna: Rabbi Dr. David Zvi Hoffmann’s Approach

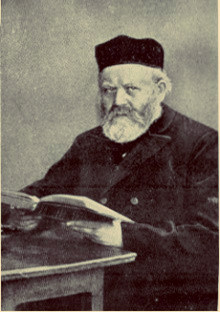

Berlin Rabbinical Seminary, 1898. R. Dr. David Z. Hoffmann was the rector from 1899-1920. Wikimedia

Preface

In an earlier essay, we considered R. Sherira Gaon and his eponymous epistle as an early medieval precursor for critical Talmud study.[1] As I noted there, R. Sherira did not produce what today would be considered a reliable history of the Mishnah’s development, but the questions he answered regarding the Mishnah and the issues he raised set the agenda for the historical study of the Mishnah.

Subsequently, for example, Maimonides devoted sections of his introductions to his Mishnah commentary and Mishneh Torah to the question of how the Mishnah developed and gained its position of authority. Some medieval scholars created chronologies of the mishnaic Sages and described their contributions to the Mishnah.[2] Leading authorities also wrote works whose main purpose was to explain the guiding principle of mishnaic and talmudic methods, yet along the way discussed the development of the Mishnah.[3] It is, however, only in the nineteenth century when the modern academic study of the Mishnah begins.

Academic Study of Mishna: 19th Century Germany

In this essay, we turn to these modern beginnings of academic Rabbinics scholarship, and more specifically, to late nineteenth-century Germany, where Rabbi Dr. David Zvi Hoffmann worked out a distinct, Orthodox approach to critical Mishnah study[4] that attempted to understand the historical development of the Mishnah from within itself and from rabbinic and non-rabbinic sources related to it. Alongside the work of other nineteenth-century Talmudists like Rabbi Dr. Zekharia Frankel, Hoffman’s scholarship laid the groundwork for twentieth century scholarship of the Mishnah. What sets Hoffmann apart from his contemporaries is his attempt to derive the history of the development of the Mishnah not only from references to its composition scattered across other traditional texts, but by carefully examining the work itself, and by “excavating” its layers.

The Historical Context of Hoffman’s Scholarship

Rabbi Dr. David Zvi Hoffmann (1843-1921) was an Orthodox rabbi who studied in Hungary and Germany under Rabbis Moshe Schick and Azriel Hildesheimer, leading rabbinic figures in the nineteenth century Hungarian and German rabbinates.[5] In keeping with the nineteenth century German Orthodox Jewish ethos of תורה עם דרך ארץ – understood as “Torah coupled with secular knowledge” – Hoffmann received his doctorate from the University of Tübingen (Germany) in 1871. Eventually, he became the rector of the Rabbinical Seminary of Berlin, an institution founded by his teacher R. Azriel Hildesheimer, that taught both rabbinical and secular subjects.

In the wake of European Jewish Emancipation, a number of Jewish scholars sought to place the study of Judaism on par with the academic study of European cultures by founding a program of study known in German as Wissenschafts des Judentums – the “Science” of Judaism. Many of Wissenschaft’s practitioners wanted to support changes in Jewish life that made it more compatible with a cultured German lifestyle. As a result, the movement was often seen negatively by traditionalists, and academically-trained Orthodox Jews like Hoffmann who did take part in Wissenschafts des Judentums saw it as their job to defend the Jewish tradition.

Academic Studies and the Reform Movement

The historical study of halakhah in particular was a major battlefield in the culture wars between reformers and traditionalists. For those who wanted to justify changes in sensitive and public aspects of Jewish life, like Sabbath observance or synagogue liturgy, the history of halakhah was not merely a dispassionate scholarly pursuit, but a venue in which to pursue change.

Through their research, reformers sought to demonstrate that Jewish practices were neither uniform nor static.[6] Many of them did so masterfully. To counter their claims, Hoffmann set out to prove that the original Oral Torah, which according to him was preserved in the Mishnah, was ancient and originally undisputed. He did so in his work on the Mishnah, Die Erste Mischna und die Controversen der Tannaim (later translated into Hebrew under the title המשנה הראשונה ופלוגתא דתנאי; and into English as The First Mishnah and the Disputes of the Tannaim).

Between R. Sherirah and R Hoffman: Demonstrating Source Criticism

In addition to arguing for the antiquity and unity of the Oral Law as represented in the Mishnah, Hoffmann also introduced source criticism to Mishnah study. As we saw in our previous essay, R. Sherira had already claimed that the Mishnah was derived from many sources, yet he did not demonstrate those sources’ existence.

Hoffmann’s claim that there is a “first Mishnah,” a Mishnah of R. Akiva, a Mishnah of R. Meir, and “our Mishnah” did not stray far from R. Sherira’s taxonomy.[7] Where he went far beyond his predecessors, however, was in his dissection of mishnaic texts and comparing them to their parallels, thereby actually showing the Mishnah to be a layered text derived from a variety of discreet sources.

1

The Antiquity of the Oral Torah: Hoffmann’s Evidence

Hoffmann used late Second Temple texts to demonstrate that the Pharisees – understood to be the ancestors of the rabbis – knew of and observed an ancient, unwritten body of practices, that is, the Oral Law. By doing so, Hoffmann approximated modern standards of historiography that also use external sources to test historical facts. Notwithstanding his Orthodoxy, in this way, Hoffman broke with the gaonic mode of reconstructing the history of Oral Torah solely from the rabbinic sources themselves.

More specifically, Hoffman refers to the following first century CE sources to attempt to prove that an unwritten law existed:

- Traditions of the fathers – According to Josephus, the Sadducees observed only written laws (Antiquities of the Jews, XIII 10, 6), while the Pharisees observed the unwritten law received as the “traditions of the fathers” (Antiquities, ibid.).

- Traditions of ‘human beings’ –In Matthew 15:2 and Mark 7:2-8, Jesus chastises the Pharisees for following the traditions of human beings, in contradistinction to the commandments of God.[8]

- Unwritten laws – Philo of Alexandia’s uses a Greek term for “unwritten laws” (αγραφοι νομοι), which suggests that Jews in fact possessed an ancient Oral Law.

Why the Evidence Falls Short

There are, however, some difficulties with Hoffmann’s evidence. For example, he assumes without question that the rabbis’ idea of Oral Torah is equivalent to Josephus’s and Philo’s “unwritten laws” / “unwritten traditions of the fathers.” This is unlikely. Instead, their “unwritten traditions” were probably customs and observances that grew from the grassroots and achieved widespread acceptance after generations of practice, but were not even claimed to be Sinaitic.[9]

Regarding Philo’s “unwritten laws”, we know now that this phrase was common in Greek philosophical writings. It meant customary law that had general communal assent and had become a norm. Violation of “unwritten law” could bring shame or sanctions on its violator. In contrast to traditional Jewish notions of Oral Torah, there is nothing divine about this form of unwritten law. Indeed, it is likely that Josephus and Philo would agree that the “unwritten laws” of the Jews, like those of the Greeks, are man-made.

It is clear that the inferences Hoffmann draws from Josephus and Philo are colored by his acceptance of the traditional ideology of Oral Torah.[10]

2

The Mishnah’s Development from Midrashic Interpretation of Torah

Hoffmann claimed that the original form of the Oral Torah was not a disembodied collection of laws, rather it was transmitted in the Midrash’s interpretive format. As a work of biblical interpretation, Midrash’s close proximity to the Written Torah’s verses make them uniquely suited for recalling the laws of the Oral Torah.[11]

According to Hoffmann, during Hillel’s lifetime (roughly the first century BCE) this method of recalling and transmitting the Oral Torah’s halakhot became too cumbersome. A new form of presenting the Oral Torah now came into being. The laws were extracted from their scriptural prooftexts and given terse formulations. This allowed them to be organized around topics. This new form was Mishnah.

Josephus’s ‘Exegetes of the law’ – Evidence?

Once again, Hoffmann attempts to prove his claim using external, non-rabbinic sources. He finds references in Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews, XVII, 6,2; 9, 3) to interpreters of the law. Hoffman argues that these exegetes were the initial midrashic interpreters who linked the Oral Torah traditions to the Written Torah before the Oral Laws were later taught separately.

Here too Hoffman’s argument is problematic. While exegetes of the law would have interpreted the Torah to teach the populace how to observe it, this does not mean that the product of their interpretation was an ancient Midrash which reflected rabbinic halakhah.[12]

A Gaonic Responsum

Hoffmann also bases his theory of the early form of Midrash giving way to Mishnah on a gaonic responsum:

שערי תשובה סימן כ וששאלת על אנשי מעשה דע מימות משה רבינו עד הלל הזקן היו שש מאות סדרי משנה כמו שנתנם הב”ה למשה בסיני ומן הלל ואילך נתמעט ונתמסכן העולם וחלשה כבודה של תורה ולא תקנו מהלל ושמאי אלא ששה סדרים בלבד והם אותם שתקנו היו אנשי משנה לא הראשונים ולא אנשי מעשה שהיו בראשונה…

Shaarei Teshuvah 20 Regarding what you asked about the “Men of Great Acts”: Know that from the time of Moses our Teacher until Hillel the Elder there were six hundred orders of the Mishnah as the Holy Blessed One gave them to Moses at Sinai. From Hillel on, the world was diminished and impoverished and the glory of the Torah weakened. From the time of Hillel and Shammai they established only six mishnaic orders. Those who established them were the “Men of the Mishnah,” not the “Early Sages” nor the “Men of Great Acts” who lived aforetime….

On the basis of this gaonic view, which also appears in Seder Tannaim v`Amoraim (Kahana edition, p. 8), Hoffmann claimed that the transition from Midrash to Mishnah took place during the generation after Shammai and Hillel. Though the source never mentions Midrash, Hoffmann takes the number 600 to refer to the halakhot attached “midrashically” to the approximately 600 commandments of the Written Torah. [13] This change, according to Hoffman, occurred because accurately transmitting the Oral Torah’s halakhot in midrashic form became impossible.

Once again, Hoffman’s reliance on traditional sources for history is not acceptable by the standards of modern historiography.[14] That said, his attempt to show that Mishnah develops out of Midrash and that its beginnings occur in the time of the Houses is interesting and even possible, even if the sources he uses do not actually prove this point. Notably, some twentieth century scholars of rabbinic literature, like Jacob Z. Lauterbach, J. N. Epstein, Chanoch Albeck, and others follow Hoffmann’s general lead, some even in more convincing ways.[15]

3

“The First Mishnah” Originated During the Second Temple Period

Hoffmann’s greatest and to some extent, most lasting contribution to critical Mishnah study was his emphasis on the stratified nature of the Mishnah, even if his analyses often fall short of today’s critical standards. Hoffmann calls the earliest stratum of the Mishnah the “first Mishnah,” and he argues that it originated prior to the Second Temple’s destruction.

The Mishna’s Description of the Seder during the Second Temple

Hoffmann points to the Passover Seder as described in the Mishnah as a good example of “first Mishnah” material. To prove this, he analyzes m. Pesahim 10:1-7. We will focus on his discussion of mishnahs 1-5.

ערבי פסחים סמוך למנחה לא יאכל אדם עד שתחשך ואפילו עני שבישראל לא יאכל עד שיסב ולא יפחתו לו מארבע כוסות של יין ואפילו מן התמחוי (פסחים י, א).

On the eve of Passover approaching Minhah time one should not eat until nightfall. Even a poor Israelite should not eat until he reclines [at the Seder]. They should not give him less than four cups of wine, even if it comes from the public kitchen supply (Pesahim 10:1).

Hoffmann claims that this is an ancient halakhah observed during Temple times based on a baraita (a tannaitic text that was not included in the Mishnah) which states:

אפילו אגריפס המלך שהוא רגיל לאכול בתשע שעות – אותו היום לא יאכל עד שתחשך

Even Agrippa the King who regularly ate at the ninth hour of the day (approaching the earliest Minhah time) on that day would not eat until nightfall” (BT, Pesahim 107b).

Since the only Agrippa known for his punctilious observance of the Torah was Agrippa I (10 BCE-44 CE), Hoffmann claims that this undisputed halakhah was sufficiently well known and in force during the early first century CE so that the king could observe it. Thus, the “first Mishnah” is “proven” to have existed before the Temple was destroyed. Of course there are numerous problems with this argument,[16] but the basic working method itself is something that could – and would – be put to more critical use by future scholars.[17]

4

Why there are Tannaitic Arguments in the Mishnah

Having proposed the existence of an uncontested “first Mishnah,” Hoffmann found it necessary to explain how tannaitic controversies developed. He also had to explain why the disputes of later tannaim did not provide a clue to the approximate date of a mishnah’s creation. For example, if R. Judah and R. Meir (c. 150-180 CE) had a dispute about a halakhic matter, why would it not be reasonable to assume they debated a contemporary issue rather than the meaning of the “first Mishnah”?

Hoffmann explains that there are three causes for late tannaitic debates:

- Different formulations of the “first Mishnah”;

- Imperfect transmission of the “first Mishnah”;

- The late tannaim’s incomplete understanding of ancient terms or halakhot in the “first Mishnah.”

I will examine each cause separately:

I. Late Tannaitic Debate Based on Different Formulations of the “First Mishnah”

As an example of a late tannaitic debate based on different formulations of the “first Mishnah,” Hoffmann analyzes m. Eduyyot 1:8:

כרשיני תרומה

Vetches [18] that have the status of heave-offering (terumah):[19]

בית שמאי אומרים שורין ושפין בטהרה ומאכילין בטומאה בית הלל אומרים שורין בטהרה ושפין ומאכילין בטומאה

The House of Shammai says: One must soak and remove their husk in purity, but one may serve them as fodder in impurity.[20] The House of Hillel says: One must soak them in purity, but one may husk and serve them as fodder in impurity.

שמאי אומר יאכלו צריד

Shammai says: They may [only] be eaten dry.

רבי עקיבא אומר כל מעשיהם בטומאה:

R. Akiba says: All actions carried out on vetches may be done in impurity.

Without getting into the content of this passage, it is easy to see that it contains (a) a debate between the Houses of Shammai and Hillel, (b) a ruling of early sage, Shammai, himself, and (c) a rejection of all these opinions by R. Akiba, who lived later than all the other cited authorities. Does this not then indicate that there was no uncontested “first Mishnah?”

Different Versions of the “First Mishna”

Basing himself on Tosefta Ma`aser Sheni 2:1, Hoffmann answers that the rulings of the “first Mishnah” were not actually contested, rather the “first Mishnah” was sometimes transmitted in different versions.

כרשינין…של תרומה

Vetches with terumah status:

בית שמיי אומ’ שורין בטהרה ושפין ומאכילין בטומאה ובית הלל אומ’ שורין ושפין בטהרה ומאכילין בטומאה דברי ר’ יהוד’

The House of Shammai Says: One soaks them in purity and husks and serves them as fodder in a state of impurity. The House of Hillel says: One soaks and husks them in a state of purity and serves them as fodder in impurity. These are the words of R. Judah.

ר’ מאיר אומר בית שמאי אומר שורין ושפין בטהר ומאכילין בטומאה ובית הלל אומ’ כל מעשיהן בטומאה אמ’

R. Meir says: The House of Shammai says: One soaks and husks them in purity and serves them as fodder in impurity. The House of Hillel says: All actions carried out on vetches may be done in impurity.

ר’ יוסי זו משנת ר’ עקיבא….

R. Yosi said: This is the Mishnah of R. Akiba….

Hoffmann sees in this Toseftan passage proof, as the Tosefta shows, that the traditions of the Houses about vetches with terumah status were known to R. Judah in one formula and to R. Meir in another. R. Yosi informs us that R. Meir’s tradition was according to R. Akiba’s Mishnah. Therefore, when “our Mishnah” cites R. Akiba as having said, “All actions carried out on vetches may be done in impurity,” he is actually repeating a version of the House of Hillel’s view that he received and accepted as accurate. What appear to be late tannaitic controversies are thus often based on repetitions of a variant of a “first Mishnah” tradition.[21]

II. Imperfect Transmission of the “First Mishnah” and Late Tannaitic Debates

In b. Gittin 85b, the Talmud states that “valid and invalid are sometimes reversed.” That is, sometimes traditions are imperfectly transmitted, saying exactly the opposite of what they were originally intended to say. Hoffmann sees in this form of imperfect transmission of the “first Mishnah” another source of later tannaitic controversies.

As one example, Hoffman points to a section mGittin 5:4:

אפוטרופוס שמינהו אבי יתומים ישבע. מינהו בית דין לא ישבע.

If the father of orphans appoints a guardian he must swear [if a situation requires it]. If a court appoints him, he need not swear.

אבא שאול אומר חלוף הדברים.

Abba Shaul says the opposite.

The “first Mishnah” clearly dealt with parent and court appointed guardians for orphans. However, the imperfect transmission of the “first Mishnah” resulted in reverse decisions about such guardians. “Our Mishnah” preserves both traditions of what the “first Mishnah” originally said.[22]

III. Incomplete Understanding of “First Mishnah” Terms and Halakhot as Causes for Late Tannaitic Debates

Just as Hoffmann was willing to agree that the “first Mishnah” was transmitted in multiple versions and occasionally imperfectly, he agrees that later tannaitic debates can occur because a “first Mishnah” halakhah or term is no longer fully understood. Therefore, the later tannaim, acting as interpreters of the “first Mishnah” argue about its proper meaning. He finds evidence for this in m. Berakhot 9:4:

הנכנס לכרך מתפלל שתים

One who enters a city should pray two prayers,

אחת בכניסתו ואחת ביציאתו

once on entering and once on departing.

בן עזאי אומר ארבע שתים בכניסתו ושתים ביציאתו

Ben Azzai says: Four [prayers]. Two when he enters and two when he departs.

ונותן הודאה לשעבר וצועק לעתיד לבא:

And he should give thanks for [what has happened] in the past and pray ardently for [what will happen] in the future.

Hoffmann reconstructs what he believes is the “first Mishnah” stratum of this mishnah, as

הנכנס לכרך מתפלל שתים ונותן הודאה לשעבר וצועק לעתיד לבא

One who enters a city should pray two prayers and give thanks for [what happened] in the past and pray ardently for what will occur in the future.

The late tannaitic debate formed around incomplete understanding of the term מתפלל שתים, “pray two, in the “first Mishnah.” The anonymous Sages understood “pray two” as “praying one prayer on entering and praying another on leaving.” Ben Azzai understood “pray two” as praying two prayers when entering the city and two prayers when leaving.

Arguments in the “First Mishnah”

Finally, Hoffmann also ceded that what he called the “first Mishnah” was not a univocal document, but did contain some points of disagreement on legal issues. The above-cited case of the Houses debate about vetches is a good example.

Hoffmann’s view is that the few instances of dispute in the “first Mishnah” are the result of the Houses occasionally using logic (סברא) to determine the correct version of a “first Mishnah” passage. This sometimes led to a debate about the halakhic content of the “correct version.” According to Hoffman this occurred infrequently enough at the outset to produce a generally accurate and undisputed presentation of most of the ancient mishnah traditions.

Conclusion

“All beginnings are hard” (Pesikta Zutrata, Yitro, 19:5). This statement is particularly apt regarding the beginnings of the modern study of the Mishnah. David Zvi Hoffmann understood that the best way to understand the Mishnah’s developmental history was to work mainly from within the text itself. Later scholars concurred with this methodology,[23] even while they attempted to move beyond Hoffman’s apologetic stance in their quest to explain, on more impartial terms, how the Mishnah came to be.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely

on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Michael Chernick holds the Deutsch Family Chair in Jewish Jurisprudence and Social Justice at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York. He received his doctorate in Rabbinics from the Bernard Revel Graduate School and his semicha from R. Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary. Chernick’s area of expertise is the Talmud. He focuses on early rabbinic legal interpretation of the Bible and is the author of A Great Voice That Did Not Cease.

Essays on Related Topics: