Five Cups of Wine at the Seder?

123rf

The Mishnah discusses drinking four cups of wine on the night of the Seder.

משנה פסחים י:א-ז ולא יפחתו לו מארבעה כוסות שליין…

מזגו לו כוס ראשון…

מזגו לו כוס שני…

מזגו לו כוס שלישי…

רביעי – גומר עליו את ההלל, ואומר עליו ברכת השיר.

m. Pesahim 10:1-7 And they are to provide him with no fewer than four cups of wine …

Once they have poured him a first cup …

Once they have poured him a second cup …

Once they have poured him a third cup …

The fourth—he completes the Hallel over it and says the Blessing of Song over it.

The fourth cup provides an occasion for completing the Hallel, whose recitation already began before the meal.

The Talmud cites a baraita that connects this final cup with the recitation of Psalm 136, according to Rabbi Tarfon, or Psalm 23, following another opinion (b. Pesahim 118a):

תנו רבנן: רביעי – גומר עליו את ההלל ואומר הלל הגדול, דברי ר’ טרפון. ויש אומרים: “ה’ רועי לא אחסר”.

Our rabbis related: The fourth—he completes the Hallel over it and says the Great Hallel, according to Rabbi Tarfon, but there are those who say, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not lack.”

The Text of the Baraita

However, when we examine two important manuscripts of b. Pesahim, we find a different version of this baraita:

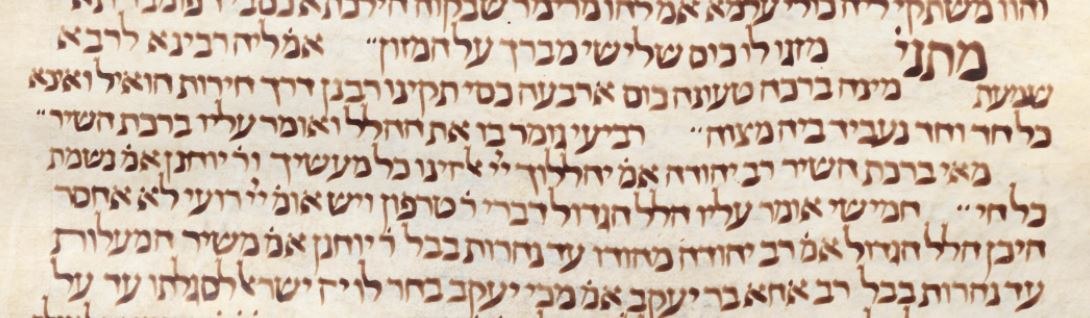

1. MS Munich 6: An Ashkenazic manuscript from the twelfth or thirteenth century.

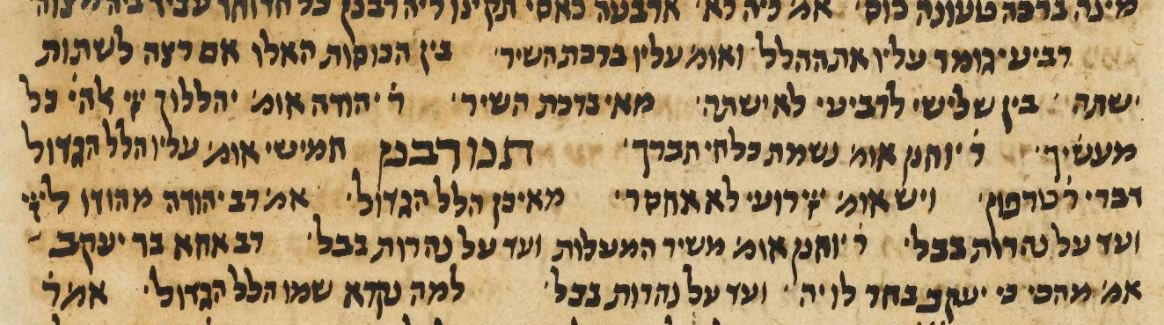

2. MS Columbia 294–295: A Yemenite manuscript,

The following table presents the text of the baraita as given in the two manuscripts alongside the printed edition:

|

דפוס וילנה

|

כתב-יד מינכן 6

|

כתב-יד קולומביה 294–295

|

|

ת”ר |

|

תנו רבנן |

| Vilna Edition | MS Munich 6 | MS Colombia 294–295 |

| Our rabbis taught: The fourth—he completes the Hallel over it and says the Great Hallel, according to Rabbi Tarfon, but there are those who say, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not lack.” |

– The fifth— he says the Great Hallel over it, according to Rabbi Tarfon, but there are those who say, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not lack.” |

Our rabbis taught: The fifth— he says the Great Hallel over it, according to Rabbi Tarfon, but there are those who say, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not lack.” |

There are two conspicuous differences (colored) between the printed version and these manuscripts. Whereas the printed text (like some other manuscripts) reads “fourth,” these manuscripts read “fifth.” The printed version also has the additional words “he completes the Hallel over it,” which it connects to the following words with a conjunctive vav.

In the version preserved in these two manuscripts, the baraita introduces a fifth cup in addition to the four mentioned in the Mishnah, and that Psalm 136 or Psalm 23 is recited over this fifth cup.

According to the printed edition, however, the baraita refers to the fourth cup already mentioned by the Mishnah, confirming that the Hallel is completed over it (as stated in the Mishnah). It adds that either Psalm 136 or Psalm 23 is recited over the same cup.

“We Read Thus”

The text of this baraita was scrutinized by leading interpreters of the Talmud, as we see from their commentaries.

רש”י: הכי גרסינן: רביעי גומר עליו את ההלל, ואומר עליו הלל הגדול.

Rashi: We read thus: “The fourth—he completes the Hallel over it and says the Great Hallel over it.”

רשב”ם: ה”ג: ת”ר רביעי גומר עליו את ההלל, ואומר עליו הלל הגדול.

Rashbam:[1] We read thus: “Our rabbis related, ‘The fourth—he completes the Hallel over it and says the Great Hallel over it.’”

תוספות (קיז ע”ב, ד”ה רביעי): רביעי אומר עליו הלל הגדול. רביעי גרסינן, ולא גרסינן חמישי.

Tosafot (117b, s.v. revi‘i): The fourth—he says the Great Hallel over it.” We read “fourth”; we do not read “fifth.”

Although they do not quote it, Rashi and Rashbam apparently knew of a different version of the baraita and stressed what they believed the correct reading ought to be using the technical “we read thus” (hachi garsinan). The content of the rejected reading is clear from the Tosafot: “we do not read ‘fifth.’”

Given Rashi’s towering influence as the Talmudic commentator par excellence, most Ashkenazi manuscripts, a sizable percentage of Sephardi ones, and the printed editions from the first printed edition of Soncino onward were influenced by his version of the Talmudic text and especially his textual notes (i.e. “we read thus”).[2] Here too, the version printed in the editions apparently originated with the emendations of Rashi, and also Rashbam, and the Tosafists.[3]

What Was the Original Reading?

The reading “fifth cup” is documented in many manuscripts and medieval works composed in a variety of places:

- Babylonia (The writings of the Geonim);[4]

- Kairouan (Rabbenu Hanan’el);

- Sephard (Rif and Rambam);

- Germany and France (as assumed in the commentaries of Rashi, Rashbam, and the Tosafists).

The word “fourth,” meanwhile, is documented only in the writings of French Rishonim and in European manuscripts heavily influenced by Rashi’s emendations. All these considerations lead to the conclusion that the older, original version was the one given in the manuscripts excerpted above: “The fifth—he says the Great Hallel over it.”

What brought Rashi, Rashbam and the Tosafists to emend the Talmudic text of the baraita? Although they did not explain their motivation for replace “fourth” cup with “fifth” cup, we can suggest some possibilities:

1. Adding a fifth cup would contradict the well-established rule, that eating and drinking is prohibited past the point of the fourth cup.[5]

2. There was no record of people drinking a fifth cup.

3. If the baraita really mentions a fifth cup, why does it not explicate whether that cup is optional, mandatory, or customary.[6]

Avoiding Even Numbers

How might we explain the original version of the baraita, which innovates a fifth cup?[7]

Some three-quarters of a century ago, the folklorist Joshua Trachtenberg suggested that the fifth cup emerged out of a fear of odd numbers.[8]

In fact, the Talmud is troubled by the question of how the rabbis could have instituted a purportedly dangerous halakhic requirement such as drinking an even number of cups of wine (b. Pesahim 109b):

היכי מתקני רבנן מידי דאתי בה לידי סכנה? והתניא: לא יאכל אדם תרי, ולא ישתה תרי, ולא יקנח תרי, ולא יעשה צרכיו תרי.

How could the rabbis establish something through which someone will endanger himself? Was it not taught: “A person should not eat in pairs; and he should not drink in pairs; and he should not wipe himself in pairs; and he should not attend to his [sexual] needs in pairs.

אמר רב נחמן: אמר קרא “ליל שמורים” (שמות יב, מב) ליל המשומר ובא מן המזיקין. רבא אמר: כוס של ברכה מצטרף לטובה ואינו מצטרף לרעה.

Rav Nahman said: The verse states: “it was a night of vigil (shimurim)” (Exodus 12:42) – a night that was continually guarded (meshumar) from demons. Rava said: A cup of blessing only joins (to make a pair) for the good, and it does not join (to make a pair) for the bad…

Apart from the Talmud’s various justifications for drinking even numbers, it is possible that the rabbis also tried to offer a practical solution to the problem – having Seder participants drink an additional, fifth cup at the Seder.[9] Psalm 136 or Psalm 23 are appropriate choices for calming a person who fears harmful preternatural powers by instilling in him faith in God.[10]

The Fifth Cup Returns

In the middle of the twentieth century, the prominent Polish born Israeli scholar and rabbi, Menachem M. Kasher (1895-1983), tried to resurrect the practice of drinking five cups of wine. His proposal was based on the explanation, which dates back to amoraic literature,[11] that the four cups were established to parallel the four terms of redemption used in the Exodus narrative: והוצאתי “I will take you out,” והצלתי “I will save you,” וגאלתי “I will redeem you,” and ולקחתי“I will take you” (Exodus 6:6-7).

In Rabbi Kasher’s view, Jews celebrating the Seder today, after the establishment of the State of Israel, should drink a fifth cup to recall the divine promise of והבאתי אתכם אל הארץ “I shall bring you to the land …” (Exodus 6:8), in recognition of the modern return to Zion.[12]

Politics aside, if in late antiquity the rabbis were willing to change the standard four cups of wine at the Seder to five in order to reassure people who feared demons, perhaps the return of Jews to Israel after a two millennia long exile might similarly justify such a change of practice today.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely

on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Footnotes

Dr. Menachem Katz is Academic Director Emeritus of the Friedberg Manuscripts Project in Jerusalem. He also lectures at the Open University of Israel and at Chemdat Hadarom College. Dr. Katz spends much of his time poring over handwritten fragments from around the world and has published widely on the Jerusalem Talmud, Aggadic literature, as well as in the field of Digital Humanities. His latest book, A Critical Edition and a Short Explanation of Talmud Yerusalmi’s Tractate Qiddushin, was published by last year (Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi & Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem 2016).

Essays on Related Topics: