Is there a Doctrine of Heresy in Rabbinic Literature?

Category:

Rabbinic Ideology and M. Sanhedrin 10:1

Rabbinic literature is more concerned with establishing norms of proper ritual practice than with determining correct theological belief;[1] the latter category of concern, however, is not entirely neglected.[2] Apart from the rabbis’ efforts to establish norms of Jewish practice that were likely based on certain theological presuppositions, some rabbinic texts do explicitly address theological concerns.[3]

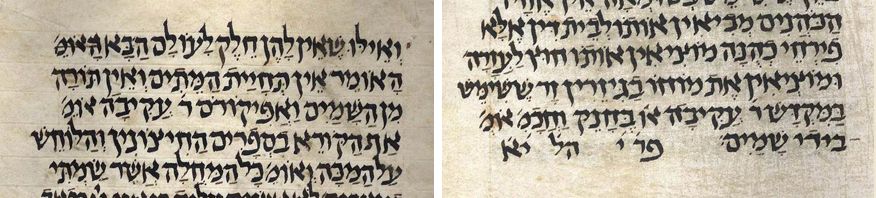

Perhaps the most well-studied of these texts is 10:1 of m. Sanhedrin. This mishnah boldly declares, אילו שאין להן חלק לעולם הבא, “These have no portion in the world to come,” and proceeds to list a number of doctrinal categories, ostensibly those that the Mishnah’s editors most vigorously opposed.

In what follows, I will demonstrate that this mishnah’s content is not a systematic expression of rabbinic theology but a peculiar amalgam of tradition and ideology.

The Introduction to the Mishnah

The text of m. Sanhedrin 10:1 – at least as it appears in the Bavli and printed editions of the Mishnah – begins with a general introductory statement:

כל ישראל יש להם חלק לעולם הבא שנאמר ועמך כלם צדיקים לעולם יירשו ארץ נצר מטעי מעשה ידי להתפאר.

All Israel have a portion in the world to come, as it is said, “Your people shall all be righteous; they shall possess the land for ever, the shoot of my planting, the work of my hands, that I might be glorified” (Isaiah 60:21).[4]

This statement is well known because it also appears as an introduction to m. Avot in some modern and medieval prayer books. The evidence suggests that this line is not part of the original text of our mishnah but is a later addition.

First, the introduction does not appear in the best Mishnah manuscripts, MSS Kaufmann and Cambridge, which begin directly with “These have no portion in the world to come . . .”

Moreover, the first word in this sentence, אילו, “These,” matches the formulaic pattern of previous and subsequent texts in m. Sanhedrin, which serve as subject headings for the various topics under consideration and are not preceded by further introductory material:

7:4

אלו הן הנסקלין . . .

These are executed by stoning . . .

9:1

אלו הן הנשרפין . . . אלו הן הנהרגין . . .

These are executed by burning . . . These are executed by beheading . . .

11:1

אלו הן הנחנקין . . .

These are executed by strangling . . .

The introductory statement in standard editions of m. Sanhedrin 10:1 interrupts this pattern, suggesting a later addition.[5]

Who Has No Portion in the World to Come?

In its earlier form m. Sanhedrin 10:1 began as follows:

ואילו שאין להן חלק לעולם הבא האומר אין תחיית המתים ואין תורה מן השמים ואפיקורוס.

And these have no portion in the world to come: the one who says, “There is no resurrection of the dead”[6] and “There is no Torah from heaven,” and an apiqoros.[7]

If we read this text as a concise statement of rabbinic doctrine from the time of the Mishnah’s editing, around 200 C.E., it is difficult to understand why these particular three items would be enumerated in preference to other common rabbinic polemical concerns.

Resurrection of the dead is not a theological problem that appears as a primary concern elsewhere in the Mishnah.[8]

Torah from heaven is the conceptual foundation of all rabbinic literature, but there is little to suggest that this was a significant issue of contention between the rabbis and their opponents.[9]

Apiqoros – The Hebrew word derives from the Greek Epikouros, the semi-legendary figure Epicurus who taught in Athens in the fourth and third centuries B.C.E. The Mishnah’s apiqoros would appear at first glance to be a follower of the Hellenistic philosophy derived from his teachings, Epicureanism, one of the schools of classical Greek philosophy. However, Epicureanism as an organized philosophical school was already in decline by the time of the Mishnah’s editing.[10]

Indeed, the apiqoros appears in only one other tradition in the Mishnah, one in Sifre Numbers, and one in Sifre Deuteronomy. [11] This can be contrasted with rabbinic polemical opponents such as the minim (sectarians) and meshummadim (apostates) that appear dozens of times in the tannaitic literature yet surprisingly are not included in our mishnah.

Locating the Historical Context

Thus, scholars have suggested that m. Sanhedrin 10:1’s most obvious polemical targets are not c. 200 C.E. rabbinic opponents of late Imperial Roman Palestine at all, but the Sadducees, a first century, pre-rabbinic sectarian group from the divisive political atmosphere of Second Temple period Judea.[12] In fact, both the first century Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, and the New Testament describe ideological disagreements between the Sadducees and their main opponents, the Pharisees, that parallel the same three issues addressed in our Mishnah.[13]

Resurrection of the Dead, which the Pharisees believed in and the Sadducees rejected, appears in the Book of Acts 23:6–8 (Revised Standard Version):

But when Paul perceived that one part were Sadducees and the other Pharisees, he cried out in the council, “Brethren, I am a Pharisee, a son of Pharisees; with respect to the hope and the resurrection of the dead I am on trial.” And when he had said this, a dissension arose between the Pharisees and the Sadducees; and the assembly was divided. For the Sadducees say that there is no resurrection, nor angel, nor spirit; but the Pharisees acknowledge them all.

Torah from Heaven – The Sadducees rejected the “traditions of the fathers,” extra-biblical precepts that the Pharisees believed to be as binding on the Jews as those precepts written explicitly in the Bible. [14] Josephus describes the dispute as follows (The Antiquities of the Jews, trans. Whiston, 13.297):

What I would now explain is this, that the Pharisees have delivered to the people a great many observances by succession from their fathers, which are not written in the laws of Moses; and for that reason it is that the Sadducees reject them, and say that we are to esteem those observances to be obligatory which are in the written word, but are not to observe what are derived from the tradition of our forefathers.

The Mishnah’s reference to “Torah from heaven” may therefore broadly include texts, such as the Mishnah itself, that later rabbinic literature refers to as the Oral Torah.[15]

Apiqoros – Josephus stresses the Sadducees’ rejection of fate (The Wars of the Jews. trans. Whiston, 2.162):

But the Sadducees…take away fate entirely, and suppose that God is not concerned in our doing or not doing what is evil; and they say, that to act what is good, or what is evil, is at men’s own choice, and that the one or the other belongs so to every one, that they may act as they please.

In this context, “fate” appears to mean something like divine providence. If so, this would explain the term apiqoros in this mishnah as well, recalling its etymological source in philosophical Epicureanism, which was well known for rejecting such ideas. The word apiqoros in this mishnah would have been intended as a satirical and pejorative reference to the Sadducees themselves, rather than to actual Jewish followers of Epicurus or of Greek philosophy.[16]

In sum, all three of the items in m. Sanhedrin 10:1’s list reflect ideological stances associated with the Sadducees.

Why is m. Sanhedrin 10:1 Stuck in the Past?

However, if m. Sanhedrin 10:1 was directed against the Sadducees, who were only active during the Second Temple period,[17] why does it appears in the Mishnah, which was compiled a century or two later?

An examination of parallel texts suggests that m. Sanhedrin 10:1’s polemical content derives from earlier sources, formulated at a time when the Sadducees were still a significant opponent. As relatively conservative transmitters of traditions, rabbinic tradents, including the Mishnah’s editors, often endeavored to preserve these older formulations yet adapted them in the process to make them more relevant to contemporary concerns.

Epicureans, Sadducees, and Denying the Resurrection and the Torah

Evidence that m. Sanhedrin 10:1 derives from earlier sources can be adduced from similar texts found in other rabbinic collections. For example, the following text appears in the rabbinic chronology Seder Olam, which is approximately contemporaneous to the Mishnah, and there is reason to think that m. Sanhedrin 10:1 is actually based on a tradition of this sort:[18]

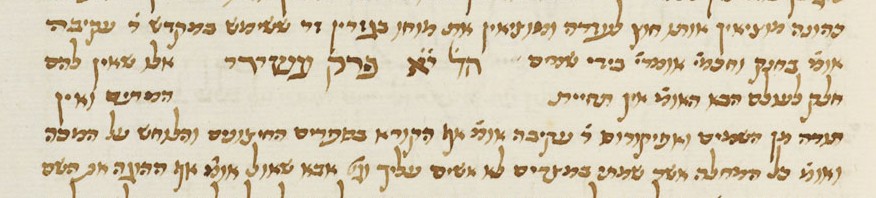

סדר עולם ג אבל מי שפרשו מדרכי ציבור כגון המינים והמשומדין והמוסורות והחניפין והאפקרסין שכפרו בתחי(ת) המי(תים) ושאמרו אין תו(רה) מן השמים גהינם נינעלת בפניהם ונידונין בתוכה לעו(לם) ולעולמי עול(מים)

Seder Olam 3 But the ones who separated from community norms, for example, the minim, and the meshummadim, and the informers, and the flatterers, and the apiqorsim who denied the resurrection of the dead and who said, “There is no Torah from heaven”: gehinnom is locked before them and they are judged within it forever and for all eternity.[19]

The highlighted phrase, “apiqorsim who denied the resurrection of the dead and who said, ‘there is no Torah from heaven’” closely parallels the text from m. Sanhedrin 10:1. This kind of close parallel in rabbinic sources generally indicates that one of the traditions derives from the other or that both derive from a common source. Rabbinic literature consists of collections of traditions that were passed down, often orally, from generation to generation, and in the process they were often reconfigured, resulting in close variants such as these.

In order to understand the relationship between these traditions, it will be helpful to consider a variant of this same phrase that appears in the Tosefta:[20]

תוספתא יג:ה אבל המינין והמשומדים והמסורות ואפיקורסין ושכפרו בתורה ושפורשין מדרכי ציבור ושכפרו בתחיית המתים וכל מי שחטא והחטיא את הרבים . . . גיהנם נינעלת בפניהם ונידונין בה לדורי דורות

t. Sanhedrin 13:5 The minim, and the meshummadim, and the informers, and apiqorsim, and those who denied the Torah, and those who separate from community norms, and those who denied the resurrection of the dead, and everyone who sinned and caused the public to sin . . . gehinnom is locked before them, and they are judged there for generation after generation.[21]

Notice that what appears in Seder Olam as a single element, “apiqorsim who denied the resurrection of the dead and who said, ‘There is no Torah from heaven,’” is presented in this Tosefta and in our Mishnah as a list of three elements.

The Hebrew syntax of the Tosefta, however, suggests that it was originally a single element that was transformed into a list over the course of its transmission. Literally, the Tosefta text reads, “apiqorsim and who denied the Torah . . . and who denied the resurrection of the dead.” The lack of explicit antecedents for the relative pronouns reads awkwardly, and would be best explained by supposing that the Tosefta text is a modification of a text such as appears in Seder Olam.

In other words, Seder Olam’s “apiqorsim who denied the resurrection of the dead and who said, ‘There is no Torah from heaven’” became, over the course of transmission, “apiqorsim and [those] who denied the resurrection of the dead and [those] who said, “There is no Torah from heaven.” This development required no more than adding a conjunction yet it changes the form of the phrase considerably.

The likelihood of this reconstruction is supported by the fact that this type of modification of early stock phrases into lists and the movement of lists into various contexts is characteristic of the development of rabbinic traditions.[22] Moreover, the word apiqoros is rare in tannaitic literature, explaining why it was further defined in the original phrase.

If this reconstruction is correct then all of the rabbinic sources that present this phrase as a list, including the Tosefta and, most importantly, our Mishnah, are later adaptations of an earlier source such as appears in Seder Olam.[23]

Preserving and Adapting Tradition

In summary, I am suggesting that the phrase “apiqorsim who deny the resurrection and the Torah” was originally an early first century C.E. anti-Sadducee slogan that slowly and incrementally made its way into the several variants preserved in the classical rabbinic corpus, changing into a list and being rearranged as it was transmitted.

This explains why the Mishnah’s compilers chose to preserve this text when its original targets, the Sadducees, had long since ceased to be significant opponents. Although the Mishnah is not especially concerned with the details of resurrection, it is very concerned with reward and punishment after death and with the idea that the Mishnah’s precepts are a legitimate expression of Torah. By rearranging the list’s elements to place these most important ideological concerns at the fore, an early anti-Sadducee slogan is in large part preserved, reflecting an editorial conservatism and respect for tradition, but repurposed to emphasize the ideological aims of the Mishnah’s editors.

The Problem of Rabbinic Heresiology

If this reconstruction is correct, then much of the material in this text reflects ideological concerns that date to centuries before the Mishnah’s compilation and only careful analysis uncovers the purposes of its deployment in the Mishnah in its current form.

The Mishnah’s polemical traditions are not always a straightforward statement of rabbinic doctrine, and certainly not a systematic rabbinic heresiology. They are rather often only a mid-point along a long chain of preservation, adaptation, and transmission of traditions thought to be authoritative and binding by their tradents.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely

on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Footnotes

Dr. David M. Grossberg is a Visiting Scholar at Cornell University. He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. He is the author of Heresy and the Formation of the Rabbinic Community (Mohr Siebeck, 2017) and the co-editor of Genesis Rabbah in Text and Context (Mohr Siebeck, 2016). He has published articles in Journal for the Study of Judaism, Henoch, and edited volumes.

Essays on Related Topics: